Provincetown is gay as f*ck

Provincetown Carnival Parade, 2024

Courtesy of Provincetown Business Guild

This story was produced in partnership with the Provincetown Business Guild and originally published in July 2025 for WUSSY Vol. 14 — order a copy!

We queers love a beach–Jacob Riis, Pensacola, the entire Isle of Lesbos, to name a few–so it’s no surprise that we congregate on the shores of Cape Cod, the flexed arm promontory that forms the eastern end of Massachusetts, a state early to embrace its LGBTQ+ community.

What is more surprising, perhaps, is how long queer folks have been gathering there–especially in Provincetown, the very tip of Cape Cod, which has been synonymous with American LGBTQ+ culture for well over a century. First drawn in with a cohort of artists and bohemians who flocked to the town beginning in the late 19th century, gays, lesbians, and trans people quickly formed year-round communities, helping to grow a flourishing art scene and establishing their own local businesses and organizations.

Provincetown–or Ptown, as it’s known familiarly–has changed over the years, evolving into a summer tourist hotspot popular with families, with soaring housing costs that threaten its longstanding creative ecosystem. But to visit Ptown today is to be immersed in the same vibrant queer culture that made it such a singular place: even amidst the families eating ice cream cones and the straight 20-something Europeans flirting with each other while on break from their foreign worker visa summer jobs, the beating heart of Ptown is still stone cold gay.

You’d know it from the rainbow flags overhead, the tourist shops hawking “I <3 My Two Dads” t-shirts, the scantily-clad lads promoting late night drag shows on bicycles. But even without all that, you’d know it merely by walking down the street, immersed in the kind of buoyant, welcoming warmth that queers knit instinctively into their communities, a form of survival that blossoms into abundance. Ptown’s LGBTQ+ culture makes ample room for the many other kinds of people who faithfully return year after year–and it lives happily alongside the town’s Portuguese heritage, the legacy of its many decades as a fishing community. But bumping up comfortably against all these other kinds of visitors and locals is a queer scene that still feels vividly alive and welcoming, from afternoon tea dances at the Boatslip to sold-out performances by the legendary Dina Martina.

You don’t have to be queer to enjoy Provincetown. But to be queer in Provincetown is to be invited inside its sunny inner-sanctum, to belong to its numinous legacy as a haven for creative misfits and gender outlaws. As these delicious archival images make clear, Ptown has long been a queer town. And as any visitor today will find, the little fishing village on the tip of Cape Cod is just as wet and wild as ever.

Before the Queers

Provincetown shoreline in winter.

CC0 licensed photo by Jonathan Desrosiers from the WordPress Photo Dictionary, 2024.

Cape Cod’s indigenous history stretches back at least 9,000 years. For millennia, the Eastern Cape was home to the Nauset, Monomoyick and Wampanoag tribes, who established semi-sedentary communities supported by the Atlantic’s bountiful fish and shellfish.

European colonists began arriving in the early 17th century–including the Mayflower, which landed Provincetown in 1620 before making its way inland–and quickly began decimating the local indigenous communities, both through intentional warfare and disease. The Wampanoag absorbed the few remaining members of the Nauset and Monomoyick tribes, and today are the federally-recognized Mashpee Wampanoag tribe, which numbers around 3,200 members. Many tribal members still live on the Cape and are actively reasserting the region’s long indigenous history.

Moby Dick(-Dock) Era

Portuguese dory fishermen relaxing in the sun, 1942.

Photo by John Collier. Library of Congress

Provincetown was formally incorporated into the British Colonies in 1727; its unoriginal name simply clarified that it was part of the Province of Massachusetts. After a shoddy attempt to farm the sandy Cape Cod soil, the Cape became a fishing region, and by 1840, Provincetown was the biggest fishing port on the Cape.

During the early 19th century, when the frenzied demand for whale baleen for corsets and whale oil to light lamps sent the whaling industry into hyperdrive, Portuguese fishermen, mostly from the Azores, began enlisting en masse on American ships. Many brought their families over from Europe–Portugal was reeling from poverty and political instability–and when cheap petroleum oil cratered the whaling industry beginning in the 1860s, they pivoted to fishing cod and other local seafood.

By 1890, Provincetown’s population had grown to 4,600 citizens, 45% of whom were of Portuguese descent. That rich cultural tradition survives today in numerous Portuguese bakeries and heritage events like the Portuguese Festival and Blessing of the Fleet every June.

The Art Party Arrives

Charles Webster Hawthorne teaching on a Provincetown pier, 1910.

Unattributed, public domain

In 1873, the railroad finally made it to Provincetown, drawing visitors from Boston and New York–especially visual artists, attracted to the beautiful landscapes, good light, and cheap boarding houses operated by local families.

In 1898, American painter Charles Webster Hawthorne, scouring New England for a bucolic spot to open the country’s first outdoor painting school, landed in Provincetown. He’d arrived on the heels of the Portland Gale, a storm that devastated the town’s fishing infrastructure, and locals leapt at the opportunity to welcome a new revenue stream. The Cape Cod School of Art opened in 1899, leading to the creation of one of America’s largest artist colonies, built by droves of artists and bohemians–many of them queer.

Okay Here’s Where Things Get Gay

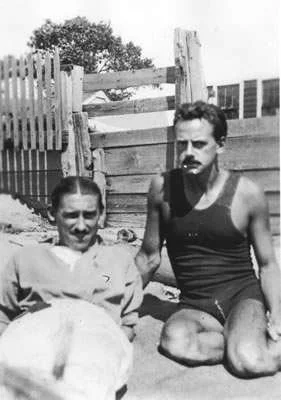

Painter Charles Demuth (left) and playwright Eugene O’Neill on a Provincetown beach, c. 1916.

Unattributed, public domain

As the creative scene bloomed in Provincetown–with new art schools, salons, and artist shows cropping up all over town–a pipeline emerged between the seaside town and New York’s epicenter of bohemia, Greenwich Village. Out of it spilled artists of all stripes, from painters to writers to actors. Many had just fled Europe, chased out by World War I, but full of its cosmopolitan ideals–among them a newfound embrace of sexual and gender fluidity. Painters Marsden Hartley and Charles Demuth, both gay, arrived in time for what Hartley called “The Great Summer of 1916.” Eugene O’Neill, still mostly a brooding mariner with aspirations of becoming a playwright, showed up around then, too, staging Bound East for Cardiff with the fledgling Provincetown Players (he’s not officially known to be queer but, you know, playwrights…). O’Neill met Demuth that summer–perhaps at Atlantic House, then as now a popular gay haunt–and they became lifelong friends; Demuth was O’Neill’s inspiration for the character Charles Marsden in Strange Interlude (1928).

More queer artists followed: poets Edna St. Vincent Millay and e.e. cummings both lived and worked in Provincetown. Tennessee Williams arrived in 1940 and promptly fell in love (with the town and multiple men), spending four summers there. He’s rumored to have written part of the Glass Menagerie at Atlantic House.

Men pose on a Provincetown beach, 1950s.

George Chapin Scott and Edward F. Bernier Collection.The History Project | Documenting LGBTQ Boston

In addition to such creative titans, queer people of all kinds made their way to Provincetown, its sand-swept remoteness forming a buffer that nourished a growing community of gay and trans people. Gay bars, drag shows, and nightclubs bloomed; many visitors bought homes and businesses and became year-round residents. Portuguese women opened their boarding-house doors to gay men and women, largely unbothered by their counter-culture tendencies so long as they paid rent on time. By the early 1950s, Provincetown had become well-known for its art, its light, and its queer scene.

Cishet Nonsense

Left: Patrons outside Weathering Heights Bar, mid-1950s.

The History Project | Documenting LGBTQ Boston

Provincetown’s queer evolution was not without its detractors. In 1951, Phil Baiona purchased the bar Weathering Heights and turned it into a gay club, featuring cabaret-style shows and drag performers, including the occasional appearance of “Bella Baiona.”

Larger than life and unapologetically gay, Baiona became the target of some Provincetown residents who resented the queerification of the once-sleepy fishing town. The next year, local government selectmen passed an ordinance barring establishments from “cater[ing] to…homosexuals of either sex.” They then attempted to strip Baiona of his liquor license, but had no luck until 1960, when a church moved in next door and the selectmen could claim the nightclub was too close to a place of worship. Weathering Heights was forced to close, but local business owners were not pleased with the selectmen’s moral grandstanding. They printed a “Shopkeeper’s Plea” in the local paper, warning officials not to chase off the “summer people,” aka gay and lesbian visitors. Shutting down queer-friendly establishments, they wrote, would risk losing “a great deal of color and quality that brings the summer source of income into this town.” That pushback helped protect Provincetown’s status as an LGBTQ+ enclave.

Baiona sold his property in 1968 and passed away a few years later, but his legacy lives on in Provincetown–as does the Weathering Heights sign, still visible behind overgrown shrubbery on Shank Painter Road.

Pride Goes Coastal

Marchers in the Provincetown Bicentennial Parade, 1976.

Courtesy Mark S. Morgan

After the Stonewall Inn riot in 1969, the gay liberation movement that cascaded across the country made its way to Provincetown. The town held its first Lesbian and Gay Liberation March in 1970–denied a permit, they marched anyways–and continues to celebrate pride every year, usually at the beginning of June.

This photo was taken during celebrations for the United States’ Bicentennial in 1976. Paul Asher-Best, a longtime Cape Cod resident who spent years living in Provincetown, recalled: “My brother, David, entered this contingent [for the] Fourth of July parade. When he went to the high school to register, the secretary who handled the event was hesitant. She finally relented, but admonished, ‘No raised fists or armbands.’ By the time we got to the center of town, our numbers had swelled considerably as ‘Proud and Gay Americans,’ with our allies joining in to march with us.”

The Tea on Tea Dance

Tea Dance Party at the Boatslip, 1978.

Courtesy of Bridget Seley Galway

Perhaps no gathering exemplifies Ptown’s long-flourishing queer scene better than tea dances at the waterside club the Boatslip. Held in the afternoon, sophisticated-sounding “tea dances” sprung up in LGBTQ+ havens beginning in the 1960s as a way to throw off police, who often raided gay gatherings at night. The Boatslip hosted Provincetown’s first tea dance in 1976; Henry Butch Mcelroy, who DJ’d that auspicious inaugural party, recalls a disco-heavy playlist that included Gloria Gaynor, Donna Summer, and Frankie Valle. Sandra Cisneros immortalized the party in her poem “Tea Dance, Provincetown, 1982.” She wrote: “But the tea dances shimmied/ miraculous as mercury./ Acrid stink of sweat and/chlorine tang of semen.”

This series from 1978 was shared by Bridget Seley Galway (right), whose mother worked at the Boatslip in the ‘70s. Galway said of the photo: “This is me and my friend and then-roommate Kevin Mahoney. I was dressed in his clothes in this photo. Going to tea dance that afternoon was spontaneous. He was my favorite dance partner. That is how we first bonded, on the dance floor. Kevin passed away in ‘88. He was like a brother. I will always miss him.”

The Boatslip still hosts afternoon tea dances daily: stop by on your next visit!

Dreamlanders in the Dunes

Divine arrives by boat for a benefit concert at the Boatslip, 1979.

Courtesy of Henry Butch Mcelroy

John Waters may have hailed from Baltimore, but he and his Dreamlanders have a deep connection with Provincetown. Waters himself washed up there in 1964, having hitchhiked his way north after high school with his girlfriend. Dreamlanders, including Divine, Cookie Mueller, and Channing Wilroy followed in subsequent summers, and Waters actually met Mink Stole in Provincetown, who quickly joined the ragtag ensemble. Waters still often spends his summers in Provincetown.

In this photo, Divine is being escorted by a crew of “sailors” to the Boatslip, where he was performing in the Hollywood Tonight’s Classic Disco fundraiser for the Provincetown Fire Department. According to Henry Butch Mcelroy–then the DJ at the Boatslip–the man in white on the right was a local fisherman who lent Divine his boat for the occasion. The grand entrance went slightly off the rails: Allegedly, Divine’s sailor escorts were blinded by flashing cameras, lost their footing, and dropped him in the surf. Sopping wet, annoyed but elegantly composed, Divine didn’t skip a beat, emerging “like a dripping wet mermaid in sequins!” as one attendee recalled on Facebook.

But Also, Lesbians

Members of The Women Innkeepers of Provincetown at a beach clambake in 1984, an event they developed into the annual gathering known as Women’s Week.

Courtesy of the Women Innkeepers of Provincetown.

As is often the case, Ptown’s LGBTQ+ history often focuses on gay men–but women have been building community there for just as long. In the 1970s, several women opened guesthouses catering to lesbians, among them Elizabeth Gabriel Brooke, owner of Gabriel’s. Brooke founded The Women Innkeepers of Provincetown to help grow and support this growing community.

In 1984, the association was looking for ways to encourage visitors during Provincetown’s slow off-season. They sent hand-written letters to past guests inviting them to an October clam-bake, complete with local entertainment. The inaugural event–pictured here, with Brooke in the front row wearing white lace-up sneakers–ultimately became Women’s Week, a lesbian gathering held in Provincetown every summer, now one of the longest-running lesbian events in the world (you can learn more in Andrea Meyerson’s 2015 documentary Clambake).

The Grand Trans Party Arrives

“The Follies!” Fashion show and performance at Fantasia Fair, c. 1985

Photo by Mariette Pathy Allen, Courtesy of photographer and Harvard University, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America

In the 1970s, as the liberation movements for women and gay people were flourishing across the world, the trans community was finding its voice, too. In 1975, members of the Cherrystones, a Boston-based trans support group, held the first Fantasia Fair in Provincetown. Organized largely by Betty Ann Lind and Ari J. Kane, a pioneering gender-queer activist and educator, Fantasia Fair was founded as a safe space for “crossdressers and transsexuals”–the nomenclature of the era–to gather and explore their identities.

The event, held in October, quickly grew in popularity, drawing attendees from across the globe as well as high-profile transgender guests like activist Virginia Prince and scholar Susan Stryker. In 1980, Fantasia Fair was even covered by Playboy Magazine. This photo from the mid-1980s was taken at the Follies! show, a staple of the week’s festivities, by Mariette Pathy Allen, a photographer renowned for her work depicting transgender communities.

Over the years, Fantasia Fair shifted to become more inclusive of trans men and non-binary people, officially changing its name in 2022 to Trans Week. The event, still held every October, is now one of Provincetown’s most beloved celebrations.

Ho, Spiritus!

Lola Flash wearing their signature milkshake cap outside Spiritus Pizza, c. 1988.

Courtesy Lola Flash

Spiritus Pizza, opened in 1971 by John “Jingles” Yingling, is about as iconic as a pizzeria and ice-cream joint could possibly be. The family-owned shop built its name on cheap slices available until 2 a.m.–an hour after the bars closed–ensuring a crush of patrons every night in the high season, as well as faithful regulars and tourists who still stream in day and night for pizza and cones.

Spiritus was twice the site of large-scale protests that highlighted tensions between Provincetown’s gay scene and the local police force. In 1986, aggressive crowd-control measures to try to clear the street outside the pizzeria led to three days of protests and nine arrests. In 1990, another protest broke out in front of Spiritus after the beloved local drag-queen Vanilla was arrested for disturbing the peace: She had just won the “Golden Plunger Award”–an annual honor bestowed on the queen who fell off the stage the most–and was celebrating by plunger-ing her trophy on cars as they passed. After she was arrested, a crowd quickly surrounded the squad car, demanding “Free Vanilla!” as she attempted to escape. The altercations–collectively known as the Spiritus Riots–revealed a seam of distrust between Provincetown’s queer community and some other long-term residents, exacerbated by the desperation and fear the AIDS crisis was stoking around the country. After Vanilla’s arrest, the town’s police department agreed to implement reforms, including hiring LGBTQ+ officers.

Through it all, Spiritus thrived. New York-based photographer Lola Flash worked there for a decade: “Jingles and all are like my family,” they say. Once, on a whim, Flash affixed a milkshake cup to their head “like a barette,” and it became something of a signature look.

Flash’s art is intimately connected to Provincetown, where they produced work like the Gay to Z series (1992) and Band AIDS, 1987, reproduced with their permission below.

Big Drag

Dina Martina, 2014.

David Belisle. Courtesy Dina Martina

A century of queer revelry has turned Provincetown into a world-famous destination for drag performance. The town’s drag bona fides stretch back to at least the ‘60s, when the famed female impersonator Lynne Carter purchased the Pilgrim House hotel, where for years she’d been performing–often as Bette Davis–at the hotel’s Madeira Club. Carter turned the venue into a popular venue for drag performance, helping to solidify Provincetown as a creative LGBTQ+ haven.

These days, you’d be remiss to visit Provincetown without catching one of the many drag shows that pack venues year-round. If you only have time for one, do yourself a favor and make it Dina Martina’s. 2025 marks her 21st summer performing in town, and she gets weirder and more wonderful with every show. “Just a charming little ashtray of a town,” she says of her beloved “Provence-town”--the two go together like sandy ass at the Dick Dock (another Provincetown bucket-list item…)

Still Here, Still Queer

Provincetown Carnival Parade, 2024

Courtesy of Provincetown Business Guild

Many things have changed over the years, but the tip of Cape Cod has remained, for over a hundred years, a vibrant center of queer culture. Gays, lesbians, trans and non-binary people, and all the communities in between have found freedom and connection amongst the dunes and cedar-shake shingles of this sun-kissed little haven.

Located in sapphire-blue Massachusetts, Provincetown may be sheltered from the worst aggressions of the Trump Administration’s Christian Nationalist agenda, but it is plagued by other, more local problems: sky-high real estate prices have jacked the costs not just to buy property here, but to rent or even visit, making it more difficult for lower-income queer people to come to Provincetown, especially young queers and queers of color. The town is actively trying to make Provincetown more accessible: check out our “how to get there” sidebar for more information on budget-friendly travel.

As the world has become more queer-friendly, LGBTQ+ have carved out summer vacation destinations in pockets all over the place. But Provincetown still offers something special, a flavor of sun-soaked, artistic, quirky community that tastes utterly unique. “The Wild West of the East,” Norman Mailer once called it. It’s worth a trip to come see why.

To read more and see our recommendations for go-to spots in Provincetown, order a copy of WUSSY Vol. 14 !