Permanent Vacation: hunx and his punx’s Seth Bogart on Daydreams, Death Trips, and the Urge to “Walk Out On This World”

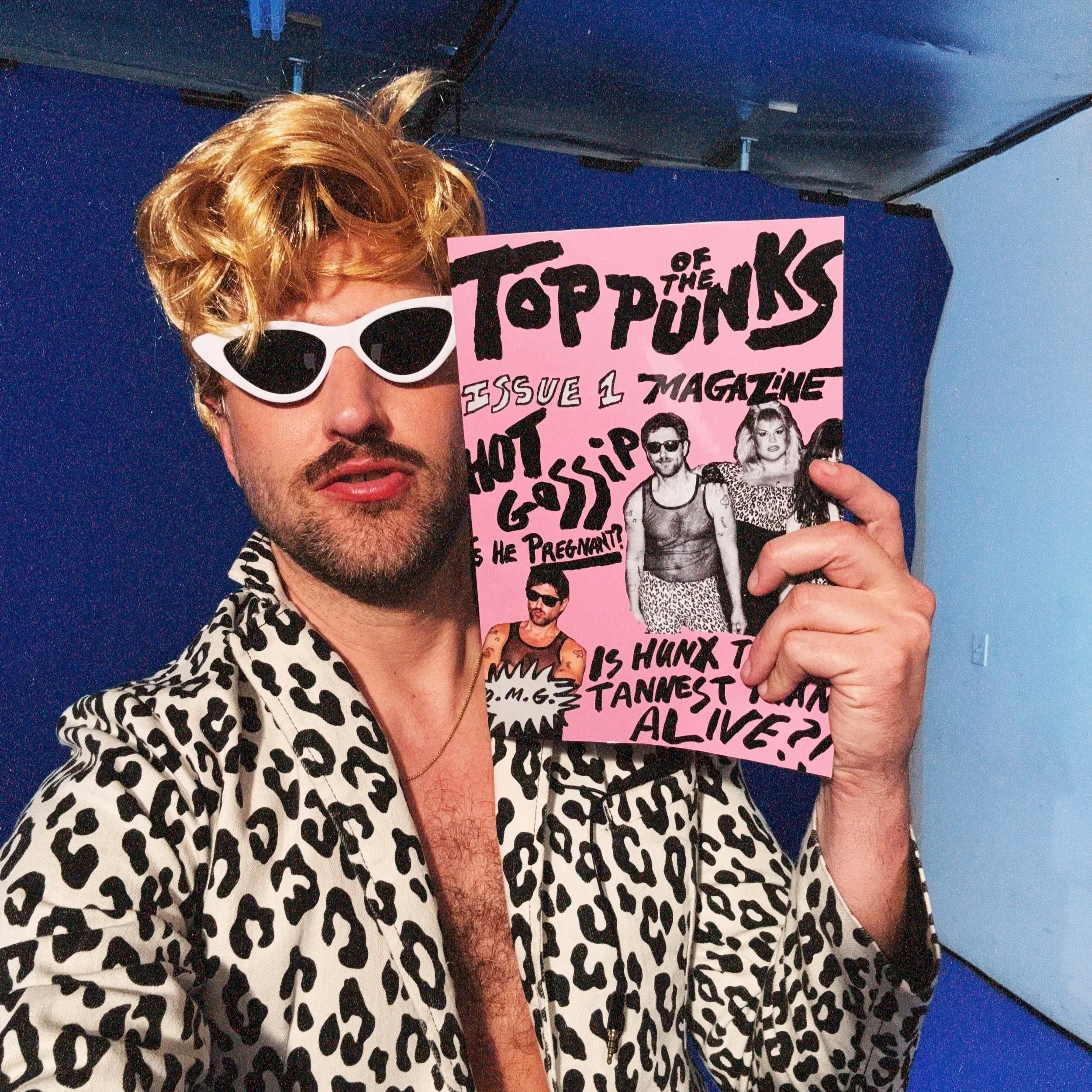

photo by Vice cooler

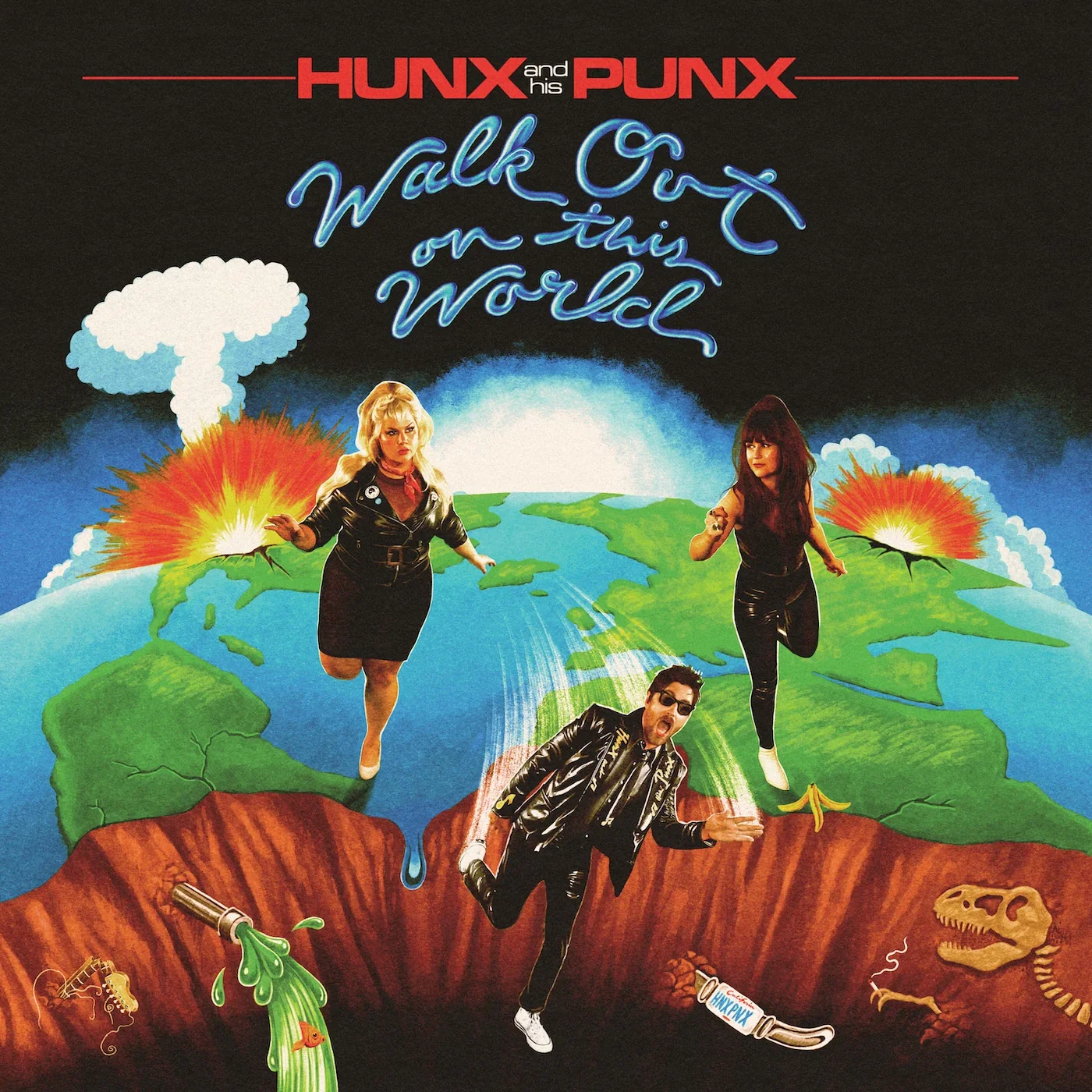

Seth Bogart is no stranger to courting catastrophe. In the face of personal tragedy, the LA-based musician and multidisciplinary artist has routinely practiced collective noisemaking as a survival mechanism, collaborative set-building as crisis management, and the wondrous camaraderie of being a slut as disaster relief. Bogart, alongside Shannon Shaw and Erin Emslie, are Hunx and His Punx, the beloved queercore band whose new album Walk Out On This World, out now via Get Better Records, is the group's first release in 12 years, after their 2019 reunion was stalled by the pandemic, the tragic death of Shaw’s fiancé Joe Haener, and multiple instances of ecological collapse, including Bogart’s home being damaged in one of the worst wildfires in the history of California.

Walk Out On This World absorbs this lingering grief into the band’s sour candy DNA, using Bogart’s bratty proclamations and Shaw’s earth-rattling howls to blast open an emergency escape hatch into a fruity punk parallel universe of their own design. In doing so, they testify to the restorative properties of community in the wake of widespread devastation. In late August I talked with Bogart about morbid fantasies, the lasting impact of Pee Wee Herman, and fighting the ongoing urge to “Walk Out On This World.”

photo by seth bogart

“ I feel like if we can't be creative and if we can't laugh, then what's the fucking point of anything? For me those are the only things that make life bearable: community, love, friendship.”

Kerosene Jones: How are you feeling about putting out a Hunx and his Punx album for the first time in 12 years?

Seth Bogart: The last time we put out a record it was called Street Punk (2013), and then we toured in Japan. After that, I was like "I don't need to do this anymore. I'm good." Shannon was super busy with her band Shannon and the Clams, and I had moved to LA, so it all just felt kind of over. I was tired of touring and doing music, so I started making artwork more seriously for the first time. Somehow five years went by, and then in 2019 a friend reached out to ask if we wanted to play John Water's birthday party at a club in Detroit, and we thought that sounded fun. The club was playing Serial Mom (1994), and L7 played, and we played, and at some point a fan handed me a joint, and then everything whooshed by too fast, and then I told jokes onstage for over an hour. I think it was some kind of cracked out lab weed or something. I kind of lost it, and started contemplating "Why are we doing this again?" But then we played a few more shows, and it was so fun, so we decided to make the record, but then a bunch of crazy shit happened.

KJ: There is a meditative, wistful energy that emerges on Walk Out On This World, more so than previous records.

SB: Well, COVID happened, which definitely slowed things down. Then we recorded the single "White Lipstick" in 2022, and the day it came out, Shannon's fiancé died. We were texting about the plan to promote it when Shannon told us that Joe was being airlifted to the hospital. An hour later he was dead. That was really fucking heavy and horrible.

Then in 2024, pretty much my whole neighborhood burned down. We had just finished the album, and we were about to start making videos. We wrote half the album in my basement. My house is still there but it's severely damaged, and I can't live there for a while. So that was also another challenging thing that happened. But I guess that's just the world now.

KJ: I've gathered that prioritizing friendship and community is important to you. I'm wondering how coming back together for this album reaffirmed that ethos?

SB: Before the fire we stopped working on the album for almost a year, because Shannon was writing really intense songs for her other project, and we convinced her to move down to LA. We didn't think it was good for her to stay in Portland. So we got her a place to live and an art studio near my art studio, which, by the way, then flooded a few months later. So we had to move again.

KJ: Mother Earth was really conspiring against you.

SB: I think the only reason we finished the album is because we love each other and wanted to hang out, even when the songs got a little more dark or serious, though they still sound kind of fun.

photo by vice cooler

Putting out music is honestly more chaotic and more work than ever before, for virtually no money. So you either have to be out of your mind, or just doing it because you have to stay alive. I feel like if we can't be creative and if we can't laugh, then what's the fucking point of anything? For me those are the only things that make life bearable: community, love, friendship.

KJ: How does that need for community relate to your ceramics and studio art practice?

SB: Most of the art I made when I was younger was related to whatever band I was in, like making sets or T-shirts for the records. Even with The Seth Bogart Show, we had music videos and elaborate paintings and sculptures and props, like the giant compact in "Eating Makeup." I've never been able to separate the audio from the visual. I haven't been able to work like that this year because my studio was at home, and everything got pretty much ruined. Not having my art studio or a stable place to live has really fucked with my head, so instead I've been writing a book, which has been kind of life-saving, and something different for me.

KJ: Can you tell me more about the book?

SB: It's a memoir. I always knew I wanted to write one, and I thought it'd be about my life amongst artists and musicians and whatever, but it's actually a lot about my dad's suicide, which happened when I was 17, and about grief, and being a slut while you're grieving.

KJ: Now that I’m thinking about self-narrativizing, combined with your history of DIY collaborative artmaking, I'm wondering how you felt about the Pee Wee Herman documentary?

“…when I'm 69 years old, I want to be hanging out with a friend and watching a movie, and then out of nowhere, they pull out a giant knife and stab me.”

photo by vice cooler

SB: I loved it. I know Matt Wolf, the filmmaker, a little bit. I met Paul Reubens maybe ten years ago, at an Elvira show at Knott's Scary Farm. He ended up hanging out with me and eight gay guys all night. He had a person from the amusement park walk us around so we could skip every line, but Paul wouldn't go into the haunted houses or any of the rides. He would just wait for us at the exit, which was kind of weird. He did this really Pee Wee thing at the end of the night, where he was like "Hey guys, I know how to get free candy. Do you want to go get some?" And we were like "Okay." And then he went into the candy store and asked for samples of everything, and ate it all, and bought nothing, and then we left. It was so cool. To be in a room with him and Elvira, my mind was exploding. I actually may go to his archive today to photograph it for a magazine, but I'm not sure. I hope I can look through all his weird porn.

KJ: In regards to the album cover art for Walk Out On This World, I'm curious about how you visualize the end of the world, and what your ideal end of the world would be?

SB: I could tell you about my death fantasies. I have two. One is pretty simple. I die on a rollercoaster, but brutally, like the train flies off the track and careens into the crowd. The other one is weirder, but when I'm 69 years old, I want to be hanging out with a friend and watching a movie, and then out of nowhere, they pull out a giant knife and stab me.

KJ: That's so tender and intimate. It's invigorating to imagine that someone you love could turn on you at any moment.

SB: I tell a lot of my friends, just in case someone at that age wants to do a double murder-suicide.

I guess my ideal end of the world doesn’t involve AI or nuclear weapons. Maybe Mother Earth will decide to self-implode.

KJ: You do have that cartoon bomb sound effect at the end of the title track, which closes the album.

photo by vice cooler

SB: Aww, you made it all the way through! That was one of the last songs that Shannon wrote. The demo was Shannon in her bedroom in the middle of the night crying, and I started crying too when I first heard it. We knew it had to be the title of the album.

KJ: I'm curious to hear more about your relationship with your bandmates as you've gotten older. Do you have any insights about working with friends or companions over a long period of time, and what it takes to sustain those relationships?

SB: I will say that I think it takes the right people, because this isn't the only band I've been in. It's not always easy to collaborate with people you've known for so long, but no shade to anyone. Collaborations can be really hard. Hunx and His Punx feels like more of a friendship than it is a band. I know that sounds silly, but I think that's the only reason we’re a band anymore, because we really love each other, and it's an excuse to spend time together and go on trips.

KJ: Speaking of trips, I want to talk more about the visual elements of this album cycle. Between the Punkette Airlines in the "No Way Out" music video, and the record’s overall emphasis on escapism, it feels like you're guiding listeners through an apocalypse travelogue. I'm also curious about the “Top of the Punks” magazine. Is that a real zine that's accompanying the album?

SB: I still haven't finished designing it, but it does exist! "Top of the Punks" is a song on the album that's a spoof of the British TV show Top of the Pops. But "Top of the Punks" is also funny, because it's like, tops and bottoms. In the video for “No Way Out” the slogan for Punkette Airlines is "Fly Away Forever."

KJ: So a permanent vacation. Blurring the lines between escapist fantasy and suicidal ideation, but in a fun and flirty way.

SB: Exactly! What is it? I don't know. It’s probably both.

KJ: Like the Bermuda Triangle, or Amelia Earhart.

SB: I love the idea of a permanent vacation. I really fucking wish it could happen. Maybe it would be boring, though, and then I'd probably want a vacation from that.

photo by sandy honig