A Story of Queer Rebirth in Three Parts: 'Physical Body of Work' by Shane Dedman

Virtual Remains, part of the 2021 Atlanta Biennial, is currently on display at the Atlanta Contemporary. Part of this exhibition includes Shane Dedman’s Physical Body of Work, a film and installation project occupying the basement space of the Contemporary. In this quiet cove lives a work that moves the viewer through the mind of a queer artist through trauma, darkness, introspection and rebirth.

Shane Dedman’s work comprises three short films. The individual films are connected through original poetry, mostly read through voice-over. Dedman takes advantage of the storytelling potential of a subtitle, cleverly pairing the image on-screen with phrases that both describe the sound and sway the mood of the scene. Each frame becomes its own poetic composition.

The first film is called Amnesia. There is the grassy sound of cicadas and crickets. On-screen are close-ups of pages faded in black mold and violet ink spread out like an autopsy on a blanket. What was once legible becomes blotched abstractions of itself. “I can no longer look back on the document”, the voice-over reads. “An archive exists, not as truth.” As the poem continues and the notebooks bleed one into the other, we can see how our past selves are not our current selves, but mere testaments of where and who we’ve been. The poem repeats “An archive exists, not as truth, but as proof.”

Next, Aporia begins. It is a black night. Silence, then a match strike. Fire burns the notebooks. “I destroyed it all”, the voice says. Fire burns, the notebook’s ashes make grim faces between the flames, the flames dance like golden-white ghosts on the wilting paper. How very Atlanta, for Dedman’s journals to be set on fire, the evidence of a former self burned away in the darkness, artistic traces gone up in smoke.

The burning feels like a reckoning, a ritual of healing. Dedman cuts ties with the past, a choice to be alive in the present. With this gesture, Dedman seems to step into themselves empty and unburdened. There is something meaningful, too, how the destruction of an archive on paper is being archived on film. The books transform, no longer useful in its original bound form, but given new crackling life. “It’s all gone”, the voice says. Behind the poem is the sound of rain, a far-off storm. We live out our painful catharsis, and then, who are we?

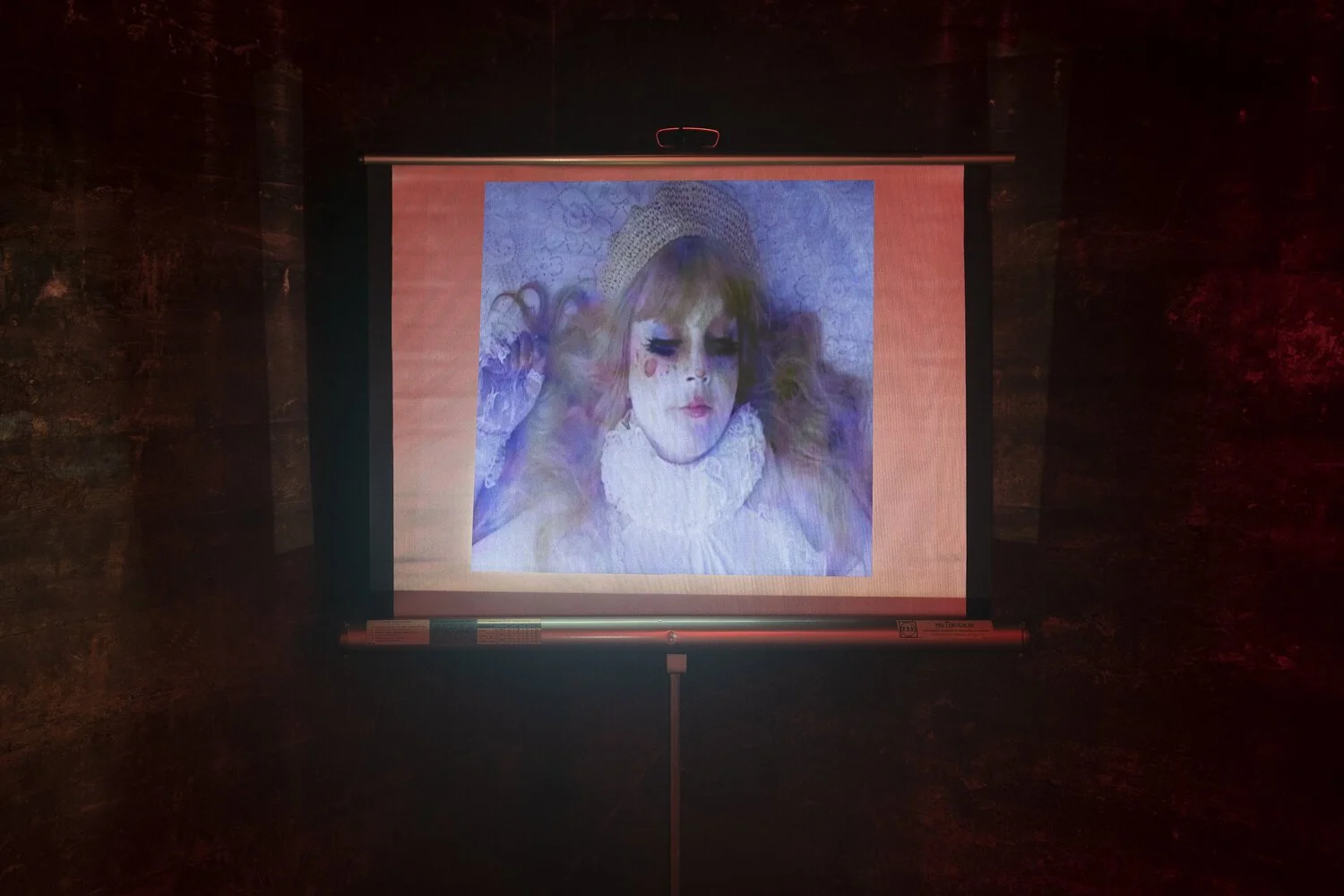

The final and longest film, Folly, plays on a neighboring screen. The viewer must reorient themselves in space for the end of the trilogy. In this chapter, we see the first body, a hand in white lace, red wavy hair, clown paint, Artemis eats berries off the branch. Artemis, our protagonist, is in a state of earthly delights, a loud chewing and burping femme wandering the dream-like landscape.

Artemis is invited to the Dedman Circus, where Dedman embodies various distinct personas interacting with each other. There is an almost vaudeville sense of humor throughout these moments. These characters perform, serve each other, irritate and bore each other. One persona charms another in a cabaret set to house music. Another reads a gloomy poem. These are the capabilities of our minds. Artemis runs through the holographic and glitching woods, toying with a stream, putting bits of the field in their hair, laying their hands over every living surface.

These films have a great deal to do with psyche, how the self deals with the self. Who are we, how do we treat ourselves, during idle thought, trauma and memory? We are contradictory and complementary, disjointed and perfectly whole. We find answers through play, through action, by fire, by air. Through a queer lens, the film is about what it feels like to make sense of these different performances of gender and identity in conjunction with performances of style and artistry.

Speaking as a queer person, non-binary particularly, I often find that we feel more ways about ourselves at any one time than we can portray on the outside. We contain multitudes. This is a magic wrinkle of our existence, a challenge and blessing. As complex as this feeling is to put into words, there is great care in the worlds Dedman renders. Dedman portrays nuance in a masterful and affirming way, a way the viewer can experience, take part in.

After the film, I was aware of how much I could let go of and part with, in order to reimagine who I could be. There’s so much to destroy, so much to honor, so much to build. Leaving the basement, it felt right to escape into the Contemporary’s garden of breath-giving rosemary. The sunlight was steady upon the plants’ reaching heads. I felt included in the freedom and space Dedman created, the new spring warmth upon me, the day’s possibilities opened up before me.

Virtual Remains, curated by TK Smith is on display at the Atlanta Contemporary until August 1, 2021.

—

Nicholas Goodly is an Atlanta-based poet and the writing editor of Wussy Magazine.

Archive

- September 2025

- August 2025

- May 2025

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015