Quentin Crisp: Remembering the Actor, Author, and Queer Pioneer

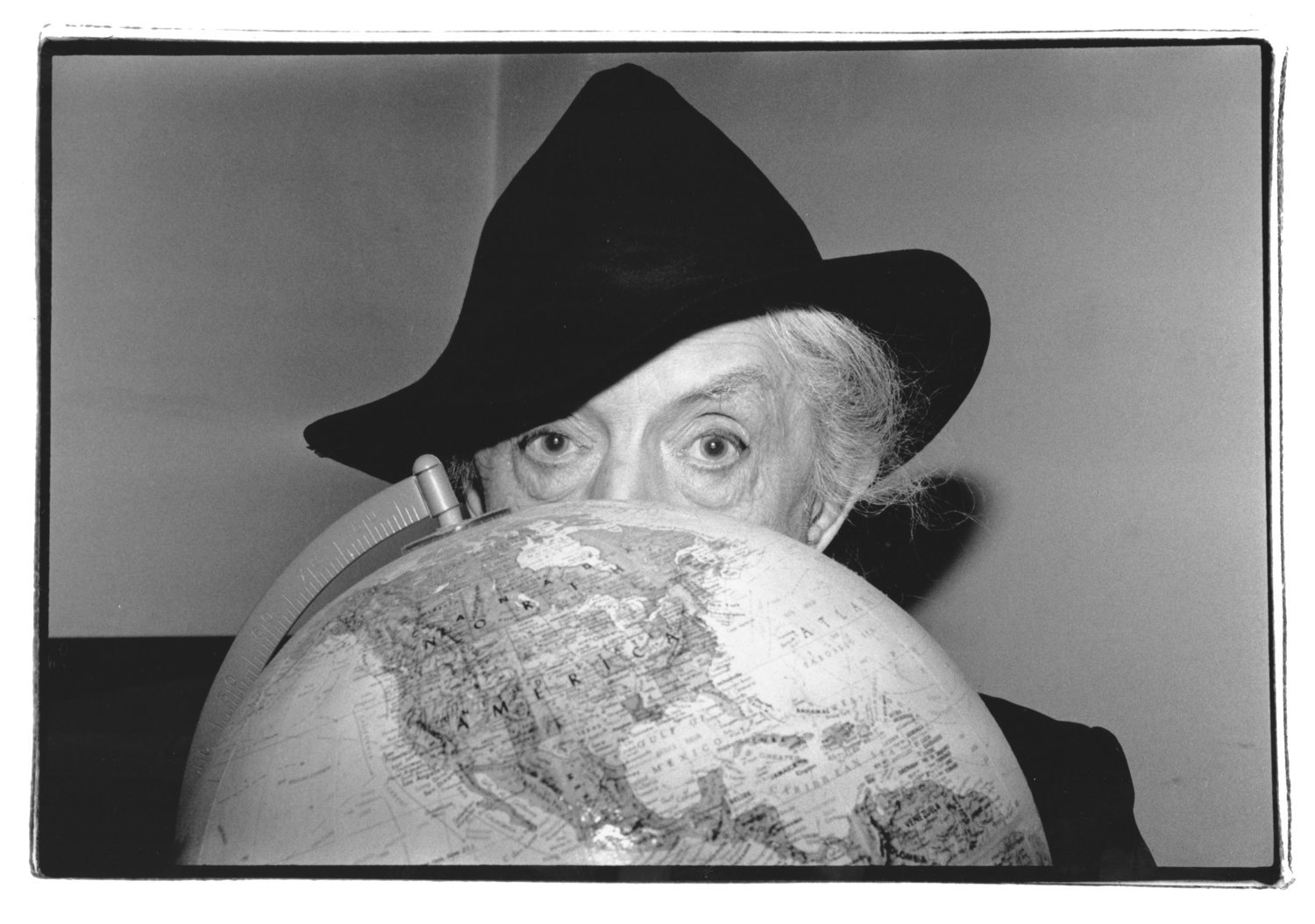

PHOTOGRAPH BY MARTIN FISHMAN © BY PHILLIP WARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

This is the way Quentin Crisp answered the phone when I called to interview him almost 20 long, dark years ago:

Ohhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh, yyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyyes???

More croak than voice, but somehow cheerful, expectant. Imagine a musician playing a slow, gliding scale from the lowest possible note to the highest on a broken, wheezing instrument, and you may start to get the idea. He was 91.

Somewhat stunned, I asked (rather unnecessarily), if I could please speak with Quentin Crisp.

“This is me,” he said in a singsong. And of course it was him. Who else would it be?

What followed, though brief, was among the best and most memorable conversations of my life. We talked about many things: I asked first about what I’d been assigned to cover for a local alt-weekly: What did he have planned for his upcoming one-man performance at Atlanta’s 7 Stages Theatre?

“Well, it’s not rrrrreeeeaaaallllllly a performance,” he began, almost apologetically. “I walk out on stage, and I tell people the only thing I know anything about. I tell them how to be happy.”

And we took it from there.

I felt a sense of freedom in speaking with him, a clear but unspoken understanding that I could ask anything, tell him anything, and that there was absolutely nothing I could say that would either shock or disinterest him. Although I’ve spoken with many people throughout my life and career, that feeling has remained singular. He is the only person I’ve ever spoken to who had something witty, insightful, memorable and stylish to say about, well, everything.

But now, just as back then when I finally sat down to write my article, I struggle a bit to convey who exactly Quentin Crisp was. Performer? Author? Actor? Wit? Icon? Celebrity? Artist? Guru? Philosopher? All fit; all fall short.

Crisp, who died in 1999 less than a year after we spoke, was most famous for the 1975 BBC television film based on his--til then--largely ignored 1968 autobiography, The Naked Civil Servant. (Crisp often referred to John Hurt, who played him in the film, as “my representative on earth.” “Any film is at least better than real life,” was one of the many ways he expressed his sincere admiration for the film that helped make him famous).

The Naked Civil Servant is a witty examination of Crisp’s life as an effeminate homosexual in London at a time when being either effeminate or homosexual was all but unheard of. (Crisp was born in 1908, little more than a decade after the trial and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for gross indecency). Although he faced harassment and abuse every single day, Crisp decided as a young man to live out his identity publicly, in a grand way, even outrageously, dying his hair scarlet, donning thick make-up and wearing colorful gender non-conforming clothes in a repressive England of the 1920s and 30s. A crowd would often spontaneously collect in the streets to follow him, hurling abuse or even getting violent.

After the success of the film, Crisp enjoyed a modest level of stardom, appearing on television talk shows, writing more books and eventually performing a popular one-man show entitled An Evening with Quentin Crisp. You can watch the entire thing on YouTube. It’s very good, and yes, he does indeed simply walk out on stage as himself to tell people how to be happy before taking questions from the audience in a hilarious and enlightening back and forth.

In 1981, at the age of 72, surprising nearly everyone, Crisp moved to New York. “I have always been American in my heart,” he claimed. “The moment I saw New York, I wanted it.” As he had for so many years in England, he lived in one tiny rented room in the then genuinely shabby Lower East Side. As in England, he liked to brag that he never cleaned his room in all the years he lived there. “After four years, the dirt doesn’t get any worse.”

TILDA SWINTON AND QUENTIN CRISP IN ORLANDO

He appeared with surprising regularity in odd places in pop culture: He was the subject of Sting’s hit song An Englishman in New York, his voice and image were used in the advertising campaign for Calvin Klein’s groundbreaking gender-neutral perfume CK-One, and he performed as Queen Elizabeth I in the 1992 film Orlando. (He claimed that in New York, if you simply stood still long enough, someone would want to photograph or interview you). In 1993, he gave a “Queen’s Speech” on the BBC on Christmas Day in England as an alternative to the annual traditional address by the real Queen of England. Allegedly, the Queen, the real one, was not pleased, but the tradition of a gay man giving an alternative queen’s address on Christmas Day has continued.

Crisp undeniably broke ground simply by living out his life as an openly gay man during a time when few could or did: he has therefore been adopted as something of a gay icon, a pioneer. The shoe fits, though for a number of reasons not always perfectly. Crisp was first and foremost a fierce individualist rather than a member of any one tribe. “I never ‘came out,’” he liked to say. “I was never in.” When he lived in New York, he actually became the subject of backlash from the gay community for some of his more outrageous statements. He often referred to heterosexuals as “real people” (as opposed to homosexuals, whom, one supposes, he must have imagined as somehow less real?). One of his attempts at wit, in which he referred to AIDS as a fad, fell flat and made him anathema in many quarters of the gay New York of the 1980s and 90s.

In some ways, you can learn much of what there is to know about Crisp simply by looking at his image. One’s self-created image should be an outward expression of the inward person, he felt, so that strangers will never be in doubt about who you are. “No one ever talks to me about the weather,” he liked to boast.

It is also well worth diving into the odd assortment of things he left behind: scores of video interviews, books, drawings, images and the odd body of assorted feature films in which he appeared. An excellent fan-created website Crisperanto preserves and disseminates his writings, recordings, witticisms and other ephemera. The film of The Naked Civil Servant makes the best introduction, and John Hurt actually played Crisp again in a 2009 sequel Englishman in New York, which covers Crisp’s later life in New York.

The posthumous final volume of Crisp’s autobiography, published only recently and called, appropriately enough, The Last Word contained the somewhat surprising revelation that towards the end of his life, Crisp identified as transgender rather than homosexual. A newly published volume of ephemera called And One More Thing contains the script of his show along with some previously uncollected poetry.

While there is no one book, article, interview, video, performance or witticism that can entirely capture who Crisp was, he does somehow manage to live on in the many fractured pieces of himself that he left behind. All the world is a stage, and Crisp still walks out onto it as himself to tell people how to be happy.

“Personally, I look neither forward, where there is doubt, nor backward, where there is regret,” he said. “I look inward and ask myself not if there is anything out in the world that I want and had better grab quickly before nightfall, but whether there is anything inside me that I have not yet unpacked. I want to be certain that, before I fold my hands and step into my coffin, what little I can do and say and be is completed.”

—

Andrew Alexander is an Atlanta-based writer and critic. His work appears regularly in Burnaway, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and other publications. He loves art, travel, bourbon and old records.

Archive

- September 2025

- August 2025

- May 2025

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015