“So That I Could Remember”: Photographer Donna Gottschalk on Capturing Real, Queer Life

DONNA GOTTSCHALK, “LESBIANS UNITED, REVOLUTIONARY WOMEN’S CONFERENCE, LIMERICK, PA” (1970), SILVER GELATIN PRINT (2017) (COURTESY LESLIE-LOHMAN MUSEUM OF GAY AND LESBIAN ART)

They sleep soundly, nestled gently into one another. The sign above them is a perfect double entendre, at once a tongue-in-cheek literalism and a political exhortation. Bathed in the light of a yawning window, their bodies remind us that queerness is, fundamentally, a joyous gesture of subversion. They sleep soundly, nestled gently into one another. The sign above them is a perfect double entendre, at once a tongue-in-cheek literalism and a political exhortation.

Bathed in the light of a yawning window, their bodies remind us that queerness is, fundamentally, a joyous gesture of subversion.

Donna Gottschalk took this photo in 1970 at the Revolutionary Women’s Conference, when she was barely twenty. Though she never considered herself a professional, she spent decades photographing the world around her, a world peopled, overwhelmingly, by queer women, as well as trans and non-binary folks, drag queens and kings, and the occasional (queer) auto mechanic. Her work, saturated in the most effusive warmth, renders visible what is so often invisible, offering queer people the rare gift of seeing ourselves.

“They were good subjects.

When people know you really like them, and that you see something very beautiful in them –

maybe it’s the very thing that has made them tortured – it’s really genuine.”

This year, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art mounted the first public exhibition of Donna’s work. I visited the show, Brave Beautiful Outlaws, and was captivated by her photos – and the simple, glorious witnessing of queer women on camera. I spoke with Donna over a series of interviews, where she generously recounted the story of her life and the lives of those who feature in her work.

DONNA GOTTSCHALK, “SELF-PORTRAIT IN MAINE” (1976), SILVER GELATIN PRINT (2017) (COURTESY LESLIE-LOHMAN MUSEUM OF GAY AND LESBIAN ART)

“I wanted to take pictures so that I could remember. I had this idea that if I became senile –

which is a very real possibility – I’d be able to spark my memory.”

Donna grew up on the hardscrabble streets of the East Village, a gritty, working-class neighborhood controlled (like most of New York) by the Italian mafia. Her mother owned her own hair salon (“the other women loved her because she was such a wicked woman”), and she raised four children largely on her own. Donna, the eldest, raced the streets with a pack of wild boys, but was also tasked with caring for her siblings, which she did with begrudging acumen (when her youngest brother Vinnie was born, she bought Dr. Spock’s book to shore up her parenting skills).

At Cooper Union – the prestigious design school where Donna applied three times before being accepted – she took photography as an intro course. She quickly fell in love with the form, shooting on a hand-me-down camera gifted from a friend. But her photography professors, all men, were unimpressed with her work and the work of women photographers generally. After visiting an exhibit of famed photographer Diane Arbus at the MoMa, Donna raved to a professor about the show. His arm around a female undergrad with whom he was having an affair, the professor scoffed, “She’s not even a real photographer.” Donna thusly concluded that art school was bullshit. She later dropped out, but a love of photography endured.

DONNA GOTTSCHALK, “ALFIE IN MARY’S DRESS” (1973), SILVER GELATIN PRINT (2017) (COURTESY LESLIE-LOHMAN MUSEUM OF GAY AND LESBIAN ART)

In the New York of Donna’s youth, queer life was shunted to the margins. The community revolved around the gay bar – a scene immortalized in Rita Mae Brown’s Rubyfruit Jungle – which offered a refuge of like-hearted women. Their tenuous safety was afforded only by stiff pay-outs to both the cops and the mob.

“The money that was made off gay people,” Donna says softly, “can never be known.” And as a photographer, these women became her subjects. “These were the only people I was talking to,” she tells me with a laugh. “My whole world was gay.”

DONNA GOTTSCHALK, “CHRIS JIMENEZ AT HOME IN QUEENS” (1969), SILVER GELATIN PRINT (2017) (COURTESY DONNA GOTTSCHALK)

Donna roomed with several women she met at the bars, plus whoever’s friend had just arrived from Kansas and needed a place to stay. Their apartment became a different kind of refuge; it became a home. “It was bad out there – the other life,” she tells me. “All of a sudden, we had friends – fifty squabbling, arguing gay women, of all stripes - it was incredible.”

This band of outsiders first became her family, and then became her subjects: treated, always, with an uncommon intimacy. Donna’s gift, I think, lies in her own comfort, the warmth of the spaces she helped to create, and the generous candor her subjects offer in return. When they look at the camera, it is clear they are looking at Donna, and that love is flowing freely in both directions.

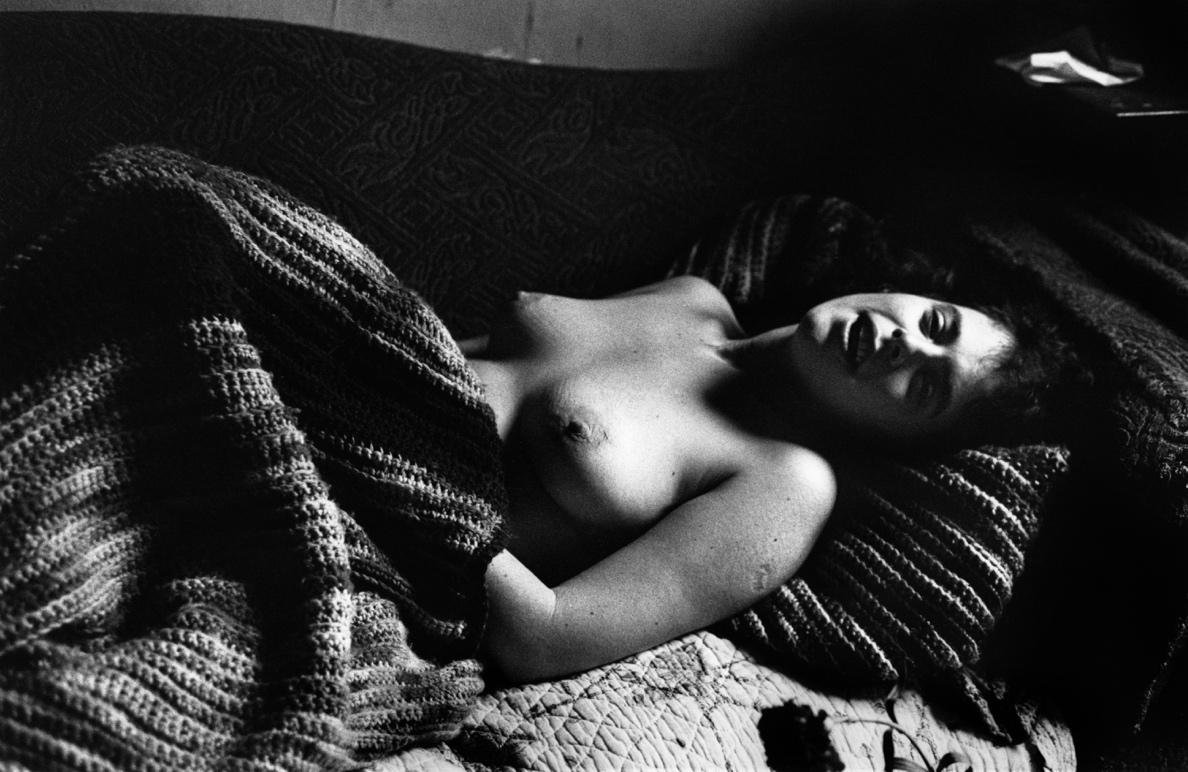

DONNA GOTTSCHALK, “MARLENE, E. 9TH ST.” (1969), SILVER GELATIN PRINT (2017) (COURTESY LESLIE-LOHMAN MUSEUM OF GAY AND LESBIAN ART)

In her late teens, Donna joined the Gay Liberation Front, which was using activist tactics learned from the civil rights movement and anti-war protests to advocate for the rights of the LGBTQ community. GLF helped organized the first pride march in the wake of the uprising at Stonewall Inn, which started as an ad hoc gathering of queer activists and ballooned into an enormous demonstration over several cities.

Through the GLF, Donna met Joan E. Biren (JEB), then another young radical lesbian activist, who would go on to become a photographer herself, as well as a famous writer, speaker, and queer cultural icon. The energy of the movement’s early days was heady, Donna tells me: “You would just go around a corner in a big meeting and you’d run into someone who just – BANG. Everybody wanted to deeply know each other… you’d wind up making love.” Then she laughs and adds, cheekily, “That didn’t always fly if you already had a lover.”

DONNA GOTTSCHALK, “DONNA AND JOAN, E. 9TH ST.” (1970), SILVER GELATIN PRINT (2017) (COURTESY DONNA GOTTSCHALK)

Donna was captivated by Joan, who in the 70s and 80s traversed the country with a slide show of lesbian photographs – affectionally known as the Dyke Show – with the dogged aim of affirming queer women’s existence. “She’s a very dynamic woman,” Donna tells me. “I saw that from the beginning.” Joan features prominently in her photography, and it was Joan who first pitched the Leslie Lohman museum to exhibit Donna’s work.

DONNA GOTTSCHALK, “JOAN, E. 9TH ST.” (1970), SILVER GELATIN PRINT (2017) (COURTESY LESLIE-LOHMAN MUSEUM OF GAY AND LESBIAN ART)

Several of Donna’s photos became iconic images of queer feminist activism – including Lesbians, United, pictured above, which circulated widely as a poster with the tagline, “Sisterhood Feels Good” – but Donna was not always given credit commensurate with the reach of her work. The Leslie Lohman show finally paid homage to the woman behind these beloved photos. Donna told me it was thrill enough just to have her GLF friends gather again for the reception, to celebrate the corner of the world they carved for themselves, captured so tenderly by Donna’s lens. “Everyone who could walk showed up…it was as if I had thrown a party and everyone showed up.”

DONNA GOTTSCHALK, “UNTITLED” (1970), SILVER GELATIN PRINT (2018) (COURTESY DONNA GOTTSCHALK)

This year, fifty years after the Stonewall uprising, the Gay Liberation Front will reconvene in New York. They’ll be joining one of New York’s alternative pride marches, which have proliferated nationwide as a protest against official city-sponsored pride parades. Donna is repulsed by the corporate takeover of what was originally a radical activist rally. “Everything we tried to fight glommed onto us,” she says. “This is a bit of a protest. We’ll have our own parade – and it’ll be like our very first.”

Donna was barely twenty when she helped organize the first parade – born out of the frenzy of Stonewall, inspired by the revolutionary fervor of the 1960s, a defiant gathering of fed-up queers who kicked open the door for an entire movement. I asked her how it felt, knowing they had been the spear tip of a movement, that they effectively launched an annual celebration of queer love the world over. She laughs. “It felt bewildering! I don’t think anyone expected the gay rights movement to be as successful as it was.” She tells me about marching in a parade in 2015, the year the Supreme Court legalized gay marriage; she and another GLF member held a banner that read, First Marchers.

“I felt like a soldier returning home from war,” she tells me. “All these beautiful young faces on either side, screaming ‘thank you, thank you’…it was the most magnificent feeling.”

The first one, she explains, had been tiny. “Well I thought it was tiny,” she adds. I can hear her laughing. “I was in the front, so I couldn’t see it was getting bigger and bigger and bigger.”

—

Rachel Garbus is a writer, performer, teacher, and who knows what all else in Brooklyn, NY, formerly of Atlanta. She does live comedy, writes essays, and is woefully inept with all plants. Follow her at @goodgraciousrachel.

Archive

- September 2025

- August 2025

- May 2025

- February 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- October 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- June 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015